GSH

Effects of Social Isolation: Oxidative Stress

The health effects of social isolation are real. Researchers have studied the effects of weeks of social isolation in mice and humans and found that it increases oxidative stress.

Why you don’t want oxidative stress

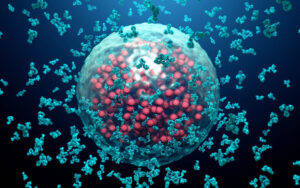

Oxidation is a normal process of metabolism. When biochemical reactions occur in your body, unstable substances known as oxidants, pro-oxidants, free radicals, reactive oxygen species, and oxy-radicals are generated. These free radicals (as we will refer to them from here on out) initiate a chain reaction of destabilizing healthy molecules if you do not have ample antioxidants to neutralize them.

A healthy, normal body has naturally occurring antioxidants like glutathione that can stop free radicals from damaging healthy cells and tissue and sometimes even repair some damage already inflicted. Certain circumstances, like social isolation, are known to cause significant oxidative stress thereby depleting the antioxidants needed to balance the oxidative reactions that are necessary for your body to produce energy. This increase in oxidation and the decrease of antioxidants needed to counter it creates a devastating situation for your cells and tissues.

Social isolation causes oxidative stress

The brain, because of its high oxygen consumption, is highly susceptible to oxidative stress, thus the potential to damage the central nervous system.

Doctors and researchers gauge oxidative stress by certain biomarkers. In mice subjected to social isolation stress for 6–8 weeks, researchers measured significant increase in multiple end products of oxidative reactions. They concluded that “6–8 weeks of social isolation stress produced oxidative damage in the brain.”

A study in rats yielded similar results. Researchers examined the effects of social isolation for eight weeks during the rearing of young rats. Studies like this are common because subjects show similar outcomes to children exposed to similar situations. The socially isolated rats had higher levels of hydrogen peroxide (chemical known to cause oxidative damage) in the prefrontal cortex (responsible primarily for speech, behavior, and reasoning) and hippocampus (responsible for memory). Social isolation also depleted levels of glutamate, which is considered “the most important transmitter for normal brain function,” as well as amino acid glutamine.

The length of time in social isolation produces more extreme oxidative stress and antioxidant depletion. Researchers compared the biomarkers of oxidative stress in the livers of rats who had been socially isolated for 21 days (short-term) and 84 days (long-term) to those who had not been socially isolated. While all socially isolated rats had more oxidative stress biomarkers, the rats in the long-term social isolation group had significantly altered oxidative stress biomarkers and damage to the liver. Other studies confirm these findings.

Social isolation depletes antioxidants

The same studies that dealt with the brains of socially isolated rodents found lower levels of glutathione. The “master antioxidant,” glutathione recharges other antioxidants. It’s critical to keeping oxidative stress down in the brain and throughout the body, as uncontrolled oxidative stress irreparably damages tissues.

In the rat study, researchers also had lower levels of the antioxidants superoxide dismutase and glutathione. That latter is critical to normal liver function as it helps to remove substances from the body — like alcohol, food, and medications — that can be damaging if they are not swiftly processed and excreted.

Glutathione depletion has numerous negative effects on your health, and symptoms can include hair loss as well as compromised function of the lungs, liver, and immune system.

How to mitigate the effects of social isolation on antioxidant levels

The studies involving social isolation and oxidative stress indicate depletion of two particular antioxidants, superoxide dismutase and glutathione.

Both antioxidants are extremely difficult to supplement as the digestive system breaks them down so they are not properly absorbed in the blood. However, some researchers suggest that eating foods like cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, barley grass, and wheat grass can help give your body the materials it needs to produce superoxide dismutase. While some superoxide dismutase supplements are available, we cannot vouch for their efficacy.

IV clinics often offer glutathione drip therapy to bypass the digestive system challenges. Liposomal glutathione also provides superior absorption. Eating a diet with ample amounts of glutathione precursor amino acids — cysteine, glutamine, and glycine — can also ensure that your body has the building blocks to make glutathione. This production process requires B vitamins, carnitine, alpha lipoic acid, and selenium, so if you are going the natural glutathione production support route, you must be cognizant of your diet as a whole.